Webinar Transcript: College Financial Aid 101

Elton Lin

Elton Lin: Hi everybody, good to have you on for our next installment of our ILUMIN webinar series. I’m excited to have Jack Wang on our show today.

I have not been on the webinars myself for quite a bit of time – so I'm excited to join in, back with everybody here and with our extended community among all of our ILUMIN families. I’m excited to engage, interact, and hear from all of you.

As we are waiting for people to roll in, if you don't mind going on to chat and letting us know where you are calling in from, I’m always excited to see where people are tuning in…

[Chat and panelists share where they’re joining the webinar from.]

Elton Lin: Continue to share where you're calling in from as we are going through and spending some time together with Jack, discussing some basics about how financial aid works, understanding merit aid – including some financial and tax strategies about how to really prepare yourself to pay for college.

I will have a conversation with Jack, and we'll go back and forth; Jack will share a few slides. If you have questions along the way, there's a Q&A box at the bottom of the panel, so go ahead and post your questions there; Anna is on our team and helping: she will come back at the end and we'll discuss all your questions. So go ahead and post all your questions there at any time – and we'll come back and answer those questions.

I’m excited to have Jack on – and we'll get started. Jack, let me do an intro of you. (Jack and I have known each other for a few years.)

Jack is a college financial aid advisor and strategist – and he works with families throughout the United States to answer (basically) two main questions about paying for college.

Number one: how do you maximize aid, even if you're “too rich”? (And the “too rich” is in quotes – however you define that. I think oftentimes families may have too much household income… but it's always in context. That's going to be different for every family, every geographic region.)

How do you maximize aid (number one)? And then number two: how do you pay for college efficiently (without wrecking your finances)? These are focal points for Jack's practice.

And Jack has been quoted in Forbes, U.S. News & World Report, Yahoo Finance… among many other publications. He's also a regular guest on personal finance podcasts, written articles, spoken to organizations such as the Boston Bar Association and the Massachusetts Society of Enrolled Agents… and he is also the host of his own Smart College Buyer podcast! So he has been working with families to help pay for college for many years.

And, Jack you also have kids who went to college as well – and you also helped (yourself) pay for their college, I presume?

Jack Wang: That's right. (Hi everyone – hello from just north of Boston!) I actually have two older sons now – mine are out of college already.

My older son actually started at a local private school here in Massachusetts, and then ended up transferring to Temple University (which is in Philadelphia). He currently lives in Philadelphia.

My younger son went to the University of Massachusetts: Amherst (here in Massachusetts). He graduated in 2020 – and he currently lives south of Boston, and works as a paralegal. And he's about to go back to law school!

So I've been through this a lot – and I work with what ends up being hundreds of families each year, throughout the United States.

Elton Lin: And you're not only well versed in helping other families, but you've also certainly done it for yourself: helped your own children navigate paying for private school – which is its own challenge, in and of itself!

As mentioned, we're going to give (all of us together) an overview of how the financial aid system works. There has been a lot of conversation about “merit aid” – so we're going to be discussing that. Jack's also going to discuss some tax strategies that make college more affordable. And then (maybe about the halfway mark) we'll open it up for questions.

I’m excited to get started! Let me begin, first, by throwing out to Jack: let's go over some basics about the costs that go into paying for college. If you don't mind, give us an overview of what is required to pay for college.

Jack Wang: Absolutely.

I want to “level set*,” because in the world of college admissions and financial aid there are a lot of terms that people get really confused about. I want to share my screen just so everybody can see and understand these terms. And if you have questions, please enter it in the Q&A box.

*[verb] To establish a baseline of mutual understanding (Wiktionary)

So let me go ahead:

Types of aid

Jack Wang: So when it comes to aid, there are two broad categories that we think of. One is “merit aid.” I'm going to talk about it a little bit but then I'll come back to this a little bit later.

Merit

Grades

Test scores

Essay/recommendations

Jack Wang: Oftentimes people think, “We get merit aid based on my student’s grades or test scores or the quality of their essay or recommendations,” or things like that (all the things that your students work with ILUMIN on: the application, essentially). But the reality is it goes far beyond that!

Major

Jack Wang: Merit aid can also be based on major. Many colleges now admit by major – so engineering students are compared with engineering students, not just with students overall.

Gender

Jack Wang: It could also be (for example) based on gender. In engineering majors, stereotypically far more males than females – versus let's say in early childhood education, which is far more females than males. But, in general, far more girls attend college today than boys.

Geography

Jack Wang: It could be based on geography: where you're from. We'll get into this a little bit more, but I can tell you right now (since most of you are in California) that in the University of California system (UCLA, UC Berkeley, UC San Diego, UC Irvine, UC whatever) and the Cal State system, it is very, very difficult for an out-of-state student to not only get into a UC school, but also extremely difficult to get aid from a UC school – because California (through your legislature) has really mandated that the aid dollars stay in-state.

So I have kids all the time (here in Massachusetts) who say “I want to go to UCLA.” (Of course, [the reason] why they want to go is the weather! I mean, it's a good school, but the weather and all this other stuff.) And after a while I'm like, “Number one: it's gonna be really hard to get in, and number two: you're an out-of-state kid, so it's next to impossible to get aid out in UCLA for an out-of-state kid!”

Or ALL of the above

Jack Wang: Or it can be any or all the above! (And one of the elements I left out here is also ethnicity; ethnicity actually matters.)

Need-based

Jack Wang: But that's merit aid. Let's talk a little bit about need-based – which is the other major pool.

Based on formula

FAFSA (FM)

CSS (IM)

Jack Wang: Need-based aid is based on a formula that the colleges use – and we'll get into this a little bit.

The schools could either use a FAFSA (what's called an “FM” – or “federal methodology” formula). If you speak to me, you'll hear me refer to, “That's a FAFSA-only school,” or an “FM school.”

Or they can end up using the CSS Profile (CSS school, profile school): IM – which is “institutional methodology.”

Income

Assets

Jack Wang: At their core, these are based on income and assets. And we'll get into a little bit here – not too much detail, but a little bit.

Not included:

Debt

Jack Wang: The important thing to know about these formulas is some of the things that are not included would be things like if you have a car loan, or you have credit card debt (or perhaps even your own student loans) – that is not counted in any way in the formulas. Oftentimes people say, “How can colleges expect me to afford this much (or not give me aid) because I have all these other debts?” Well, quite frankly, they don't care.

Cost of living

Jack Wang: Also cost-of-living differences don't matter. For example, most of you in California, you're in a very high-cost area. Me in Boston as well. (And really most major metropolitan cities around the U.S. are generally higher costs – as opposed to living in the middle of nowhere of Wyoming or something.) There's no adjustment for that.

I've heard that, too: “Don't they know how much it costs to live here in L.A.?!” Yes – and they don't care. [Laughs.] I hate to say it that way, but it's true: there's no adjustment for that.

So those are the two main types of aid.

Need-based aid

Jack Wang: Now I will get back to merit in just a moment, but I want to talk a little bit about “need-based” aid first – and how that works.

FM and IM

Income

Assets

Parent AND student

Jack Wang: We talked about the two formulas: FM and IM. Generally they're based on the incoming assets of both the parent and the student. Both formulas look at those things together.

Key differences

Jack Wang: But there are some key differences between the formulas.

Untaxed income

Jack Wang: For example: untaxed income. The FM (or the FAFSA) formula is actually about to change… but, for example, if you contribute to a 401(k) at work, not only do you save for retirement (which is a good thing) but you're also lowering your take-home income – because you're saving part of your money into a 401(k). Same thing is true if you open up an FSA (a flex savings account) or an HSA (health savings account) – those type of things.

But for financial aid purposes, especially at CSS (or IM) schools – and, by the way, IM schools in California would be Southern Cal, Santa Clara, Stanford, University of San Diego… things like that – the way financial aid looks at it is: “Yes, you're contributing this much money to your 401(k), but you still earn the money. You still got paid the money – but you chose to put it over there.” So (especially in IM schools) the more you contribute to your 401(k) actually does not lower your income for financial aid purposes – because they treat it as if you “earn” the money (because, quite frankly, you did).

So there are some differences there.

Multiple kids in family

Jack Wang: The other thing is multiple kids in families – especially when you have more than one child going to college at the same time. The old rule under FAFSA used to be (and it ended this year) that if you have two kids in college at the same time, they would take whatever colleges think you can contribute and divide it by two (if you have two kids) – or three, or however many. Well, that “divided by” mechanism is going away.

So whereas before, if you had more than one kid in college at the same time, you almost got a multi-kid discount (if you will)… that's going away. But that still exists for “profile” (or IM) schools.

Primary residence equity

Jack Wang: The value of your “primary residence.” For FAFSA-only schools, it doesn't matter if your house (the house you live in) is worth a million dollars – or millions of dollars. For FAFSA schools they don't count it.

But they do count it for “profile” schools: IM schools, or CSS Profile schools. So you might have low income and not a lot of money in the bank… but let's say you inherited a house from your grandparents or something, and that house is worth ten million dollars. Well, that's treated as if it's $10,000,000 in your bank account!

So there are these differences.

Divorced parents

Jack Wang: And then lastly, one other major area of difference is when you have divorced families.

In the case of FAFSA schools, only one parent files a FAFSA. Now the rules around that are changing (as to which parent files) – but it's still only one parent.

In profile schools, for the most part both parents file. The custodial parent files their income assets, and then the non-custodial parent also files their income assets. And then. if both of those divorced parents have since remarried, you're potentially adding up four parents’ worth of income and assets when determining financial aid!

So if you're in a divorced family, then the formula treats you very, very differently.

Elton Lin: I think what you're saying here is that there are so many different inputs – and maybe you're alluding to the fact that there are also so many different approaches to how to tell your story (in some sense) on the FAFSA and/or the CSS profile.

Just to address a quick question: just to clarify with regards to the 401(k) contributions. That is still calculated in the total estimated family contribution, correct? Even though you're contributing to a 401(k), it's still counted as “income” (even though you don't really have ready access to that cash)? Can you clarify that?

Jack Wang: Yeah, that's exactly right.

On the FAFSA side, this is one of the rule changes. It used to be that (on the FAFSA side) if you contributed to a 401(k) (when I say 401(k) I mean 401(k), 403(b), a 457 – any kind of workplace retirement plan that's pre-tax) that money would be added back as income because, again, you earned the money; you chose to put it over there.

But under FAFSA rules that's actually going away. On the FAFSA side, going forward, any money you contribute to a 401k now will no longer be added back. So if you contribute a lot of money to a 401k each year, then your income actually will go down.

But on the CSS side, that adding back of the contribution still happens – and that's not changing.

So to your point, Elton, there are a lot of these little pretty detailed, highly technical “inputs”… but the point is that you can end up getting very different results for financial aid at certain schools. At some schools that maybe only use FAFSA you might get a ton of aid, and your finances haven't changed but then when you fill out the CSS you get almost no aid – because of the differences of how they treat these little things. (Vice versa could be true also.)

It's important to understand how colleges view your finances as part of the strategy – and we can talk more about that later.

Elton Lin: And just to clarify: the CSS profile is submitted primarily to private schools, and the FAFSA is submitted primarily to public schools? Is that correct?

Jack Wang:

Correct, primarily. There are obviously some exceptions: your “Public Ivies.” I'm sure people have heard the term “Ivy League,” but your “Public Ivies”: namely, University of Michigan, University of Virginia, University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill (those are three of your “Public Ivies”) – even though they're public schools, they also do require the CSS profile. So there are some exceptions.

Need-based aid calculation

Cost of attendance

Less: merit scholarships

Equals: net price

Less: expected family contribution (EFC) / SAI

Equals: financial aid eligibility

Jack Wang: Moving on real quick: let's just talk about what they do with this information.

Colleges apply this basic formula: they take the cost of attendance (remember, that's the “sticker price”) and they subtract out, first, merit scholarships. (If there are any; don't forget: not every school offers merit scholarships.) And that equals something called “net price.” (As you're going through this process, families, you might often see a term that says “average net price” – which is typically the average of the formula you see: cost of attendance minus whatever scholarships they receive.)

Colleges then subtract out your “expected family contribution,” or EFC – which is based on the formula we just talked about: based on income and assets and those little technical details. And that term EFC is about to go away, to be replaced by SAI, or “student aid index.” But the bottom line is the EFC is how much the college thinks you can afford per year, per student.

Once you take the net price and you subtract out the EFC, what you're left with is what's called “financial aid eligibility.” It doesn’t say how much financial aid you're going to get; it's financial aid eligibility.

So this is the basic formula of how schools use this number.

Sometimes this is where parents think, “I'm too rich to get aid!” For example, at the UC schools, if you're an in-state resident I think it’s around a $36,000 cost of attendance, give or take. Let's just say there's no scholarship. But let's say your income and assets are such that the colleges think you can afford $60,000 a year. Well 36 minus 60 is negative… so that's why at some of these schools you don't get any aid – because what they're seeing is, “Well, you can afford more than we even cost!” So that happens.

That's how need-based aid generally works.

Where does aid come from?

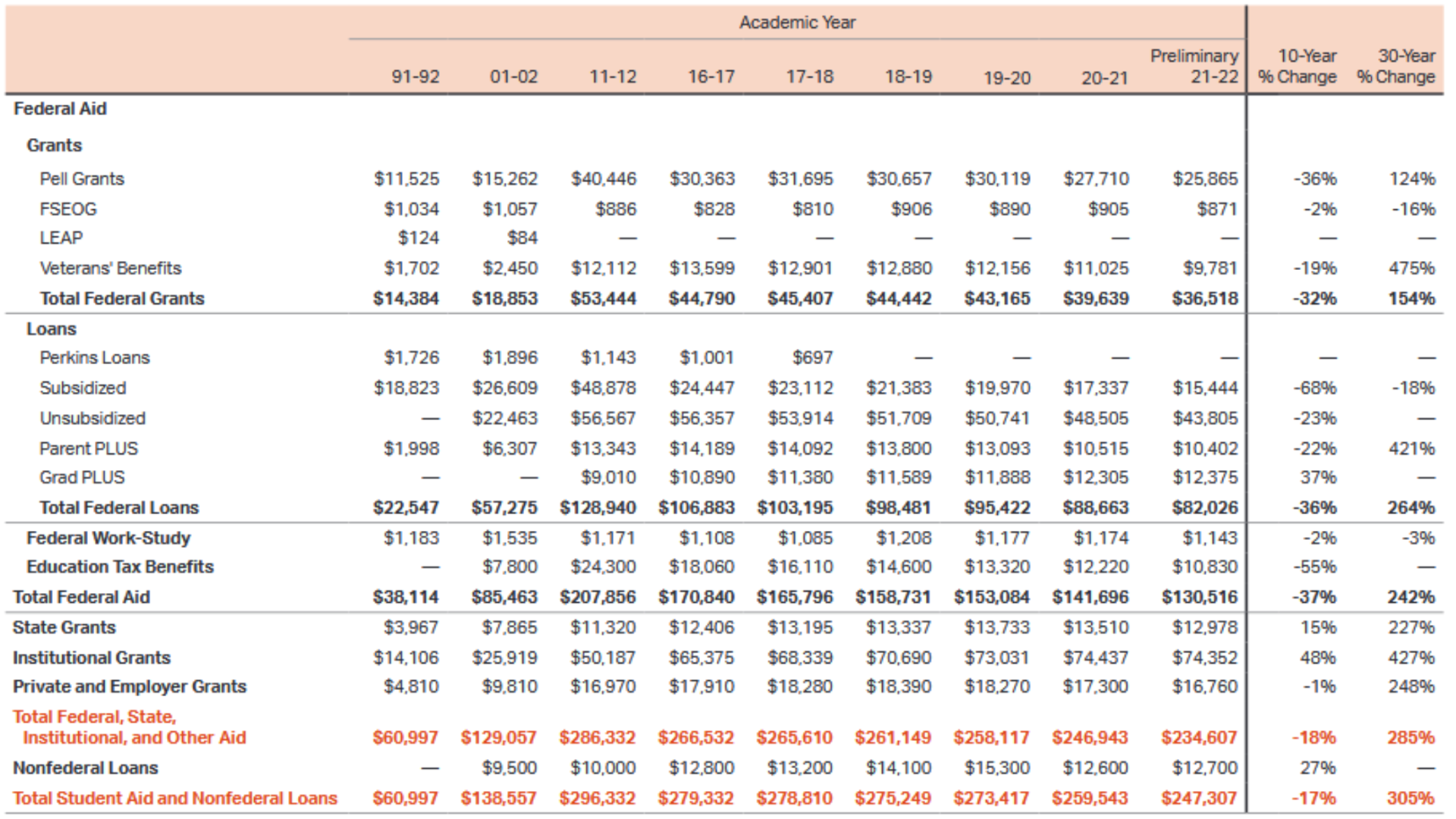

Total Student Aid and Nonfederal Loans in 2021 Dollars (in Millions), Undergraduate and Graduate Students Combined, 1991-92 to 2021-22, Selected Years

Jack Wang: I want to talk a little bit about where aid comes from – and this really gets back to the merit aid point. This is actually from the College Board – and you may be familiar with the College Board; they're the people who run the SAT, as well as administer the AP exams. And every year they do a report on college-student pricing and aid.

I know there are a lot of numbers, but [at the bottom of] that top section [in the rightmost row (2021-22) it] says “total federal grants.” It's $36.5 billion; $36.518 billion. “Loans” are $82 billion. And then there's something called “work study” – which is only $1 billion. This is really the on-campus job. And then “educational tax benefits” – which we'll talk about later – that's almost $11 billion. But total aid from the federal government is $130 billion.

If you ask the question, “Where does aid come from?” the vast majority of aid comes from the federal government. Except that the vast majority of that number is in the form of loans: $82 billion of the $130 billion a year comes in the form of loans. Which is also why (by the way) “Student loans total 1.6 trillion!” – you see the headlines, etc., etc.

If you go below that: “state grants,” just under $13 billion. This would be from the state of California, or from the state of Massachusetts, for their residents. Then “institutional grants” is $74 billion. That is from the colleges themselves: whether it's scholarships, grants or otherwise. Then “private employer grants” is $16 billion. This would be people saying, “What if I apply for scholarships from a local foundation or a local company (or whatever)?” It's a relatively small part of the overall pie.

But take a step back for a moment and think about where grant money and scholarships come from – because you don't have to pay that back. What's the largest source of grant money or scholarship money? It's not the federal government. It's not the states. It is not outside scholarships that your kids may or may not be applying for right now. By far the largest source of grant money/gift aid/scholarships/whatever money that you don't have to pay back comes from the colleges themselves.

How to get the most aid?

Jack Wang: As a result, when you think about how to get the most aid – this is what I work with families on.

Most families ask:

Jack Wang: If you think about what your student and what guidance counselors are talking about, and the questions that you might be asking, most families are focused on this:

Where can my student be accepted?

Jack Wang: “Where can my student be accepted?” Or, “What do I need to do to get accepted?” This is where you get questions like, “Is this college test-optional or not?” or, “How many letters of recommendation do I need?” or, “How many essays do I need to write?” or, “Do they accept the Common App?” or, “How do the schools view extracurriculars?” I'm sure you guys have all talked about those questions.

Most families should ask:

Jack Wang: But if you're looking to get the most aid, the question you need to ask is different:

Which colleges will offer my student the most aid?

Jack Wang: It is not where can you get accepted. It's, “Which colleges will offer your student the most aid?” Which is a completely different question – with a completely different answer!

How aid really works

Jack Wang: The reason for that is because I want to talk about how aid really, really works.

Elton Lin: I'm sorry Jack; I think it's a really important point that you're making here – because when we're working with students and we're talking about finding ways to pay for school, I think oftentimes students (as well as families) are asking a lot of, “Where do I find scholarships?” They get the admission decision and they go off and they feel like they want to find some kind of scholarship source. They end up applying to a lot of scholarships.

And that is a way to find some money… but really the thesis of what you're saying here is that the majority of money will come directly from the schools you apply to – and then, perhaps, thinking about which schools will actually give you the most money (and perhaps rearranging your college choices based on that… if needing to get money in order to pay for college is of utmost importance – which it is for a lot of families).

I want to make sure we emphasize that – if that's really what you're trying to say. Is that correct?

Jack Wang: Absolutely. And what you're saying gets to this point.

By the way, bonus points if anybody recognizes this movie; this is from (I think) the late 80s [1991] – or the name of this actor: the name of the movie or the name of the actor.

But in this scene in this movie, another actor in this movie is posing a question to this actor you see on the screen., and this actor you see on the screen… “City Slickers”! Very good, the movie is City Slickers.” And the actor's name is the late Jack Palance. The question that's posed to him in the scene is sort of like, “What's the meaning of life?” or, “what's the way to happiness?”

And his answer is: it's the one thing. He holds up his finger.

I use this as an example because college aid – whether you're too rich, too poor, whatever – really boils down to one thing: and that is not how much your student wants to go to that school. It’s not about your son or daughter saying, “I really want to go to Stanford! I really want to go to Berkeley! I really want to go to UCLA!” – whatever the case may be. It’s all about how much that school wants your student!

And I do not mean accepted. Remember earlier, I said for merit aid most people think it's based on grades and test scores and essays and things like that. The reality – and that is true for a lot of schools – is that your student is compared to every other student who applies to that school. But schools have different goals.

It could be based on: they're adding this major, so they need more kids in this major. For example, at Duquesne in Pittsburgh they're really expanding their College of Engineering. I just read that Skidmore College in New York is adding a College of Health Sciences, which they don't have yet – and they're investing like $50 million to build a new building. Well, if your son or daughter wants to study health sciences (nursing, whatever) and is willing to go across the country to Skidmore then – all things all other things being well – they might get a bigger scholarship, because the school's trying to get students into that program.

It could be based on ethnicity. It can be based on geography. I mentioned earlier how UC schools are not very friendly to out-of-state students. I don't mean that in a negative way, but it's very hard for out-of-state students to get into a UC school. And also basically impossible to get aid.

The same is true for Texas. The same is true for Florida. The same is true for North Carolina: Chapel Hill.

But there are other schools: University of Maine, University of South Carolina, University of Alabama, University of Mississippi, Arizona State… They're looking for out-of-state students. They want out-of-state students. So at some of these schools, if you have a high-achieving student, you can go to an out-of-state college (in some of these places) for less money than you would have paid in-state.

Or it could be gender. Or all of these things combined. The more your student can help the college achieve their goals, the more aid you get.

Now every school has different goals, sure, but I can tell you that I have a client here (from Massachusetts) whose daughter goes to a well-known private college in California. The family makes $600,000 a year. (In most places that's not poor. I don't know… in California that might be middle-class; but $600,000 a year is not “poor.”) And this college does not give merit aid. But this college gave this family twenty thousand dollars of financial “need-based” aid.

I just told you it's based on income and assets. How could that possibly be? How can a family that makes $600,000 a year get financial aid? Well, because the student “checked” a lot of boxes for that college: that student helped that college meet a number of what we call “institutional priorities.” So that college really wanted that student!

The reality is the people who run colleges are not idiots. If you're trying to go into a college and you're willing to pay full “sticker price” (which could be $80,000 or $90,000 a year) they're more than happy to let you pay full “sticker price.” But make no mistake: if you get in for full “sticker price,” they did not really want you.

Doesn't mean your student won't do well. Doesn't mean they won’t get a great education. They can do well; they get a great education. But what it really means is that your student didn't really stand out in the applicant pool – because the students that they really, truly want (for whatever reason they want them) are the ones who actually got the aid.

Elton Lin: If I can qualify that statement by saying that I think the point that you're making is that every institution has their particular institutional goals – whether it's more students from a particular geographic area (a common example is, say, North Dakota) or a new engineering department, and there are not enough students…

I have a specific student of my own who is applying into a fashion program – and was also offered (similar to the family you were describing) some aid to go.

Perhaps there's this aspect to where they're looking for particular students… so it's not a student that they don't want. And certainly, once they admit you, they want you to come – and I think (from an admissions perspective) that is very clear. It's not so much that they don't want you; it's that they are motivated to use aid to, perhaps, get more of a particular type of student to come. I think that's maybe the differentiating factor that you have here.

I feel like the follow-up question is (without getting into trying to overly profile every university: “Do they need more swimmers? Do they need more of this and that?”), “How does a family (or a student) approach, perhaps, finding what type of college is looking for them – and maybe even try to target some of those colleges that are looking for that type of student?

Jack Wang: That's a great question. And that is a challenge; I'm not going to say that it’s not, because it's even a challenge for me – and I do this professionally!

You sort of have to do the opposite of what most families do. When most families go through this process and say, “My son or daughter wants to study geology,” so you might Google top schools for geology – or U.S. News & World Report rankings for the best schools in geology, whatever the case may be. And that's obviously a very common way of going. But if a school is really well-known for geology, they probably have an established program – and so they might not be looking for more students to really expand.

It's hard. I'm not saying that you should go to a school that is just starting a geology program – because then you worry, “Can they get jobs?” and stuff. (But that's kind of an unfounded fear.) You really have to look at where your student is truly different.

I'm working with a Hispanic family right now, and I explained this to them. They're like, “We're thinking about this college.” I said, “There are actually a lot of Hispanic students there. Where you actually get most aid is you want your son or daughter to be the only Hispanic kid.” Maybe not to that extreme, but that's the basic idea: because they stand out. They're different than what the rest of the college [student body] is. And so as colleges try and round out their student bodies…

It is very difficult… but every so often you hear, “XYZ College is investing in a brand new building!” That's an indicator that XYZ College is starting a new major. And things like that.

In the case of Skidmore in New York they're dropping $50 million on this building – and I can guarantee you that when a college invests $50 million in a building, they're trying to attract students. They're also going to make sure that your son and daughter can get a job afterwards. You don't make that kind of investment and then just leave it for nothing! (That's why I said not getting the job afterwards is sort of an unfounded fear.)

It's hard. I'm not gonna lie; it is hard. But the question that's often not asked during tours [those not run by student employees] or whatever (because if you think about tours, they talk about, “We accept students in this GPA range, in this SAT,” blah blah blah) is “Okay, it's great, but what are you really looking for? What kind of student are you really trying to attract? What majors are you trying to build up or add or whatever?”

It’s never asked in the information sessions. But you can ask [if the tour guide is not a student employee, who wouldn’t know administration’s priorities].

Elton Lin: From our college advisory perspective, this is certainly not our expertise – and I think this is why we're trying to bring people like you, Jack, onto the program. But because there's such a sea of different information, if I'm a family thinking about where to begin, oftentimes it's a little bit overwhelming!

We try to advise families to begin, “Which schools might be more apt to providing merit aid?” And I always try to tell families: “Begin with the academic level.” If your students is at a GPA or test score profile that is at least in the top 50th percentile (or let's just say even better: in the top third of the applicant pool) then you're more apt to getting merit aid.

Because if you're a university trying to build your class, you do need some students who are higher-performing in order to, perhaps, “round out” some of those institutional metrics: average SAT scores, average GPA… to try to make sure that there are enough of those students in the class. And so they may use merit aid to try to attract some of those students to come.

As it relates to some of the other factors, I think it's hard to nail some of those things down. And if you're not at an appropriate academic profile, then I think some of those other factors become difficult. So begin with your academic profile – and make sure that your student is (I would say) at least in the top third of the applicant pool. I think that's a good place to start.

Also, there is some public data about which schools provide more merit aid to students who don't get need-based aid. Is that correct, Jack?

Jack Wang: There is. And I want to just touch upon the academic side of it.

It's a great way to start. I've sat in enough of these tours and information sessions to know that they present: “Last year we accepted kids who had an SAT at this range or this range, or ACT of this, or GPA of that,” whatever. But along those lines, the question that is never asked: “Great, thanks so much for telling me that last year your average SAT range was this, but tell me what was the minimum to get into the range of getting a merit scholarship?” Or, “The kid who got a merit scholarship: what did their scores look like?” That's never asked.

And also, because a lot of colleges now admit by major, they might say, “The college overall was [in] this range.” But if your son or daughter is going to the College of Engineering, College of Business, or something else, that range can be significantly different. You're not looking at, “I'm above average here!” You might have to be above a much higher number – that of the engineering majors, the computer science majors, or the business majors.

You can ask those questions in these information sessions. They’re never asked! I've sat through so many of these – and nobody's ever asked!

You can ask what percentage of kids get merit scholarships. A lot of parents mistakenly think, “If my kid gets in, they get a merit scholarship!” And colleges sort of feed that perception: a lot of colleges say, “90% of our students got some sort of aid.” But you can ask, “What percentage of students actually got merit aid scholarships?” It's not 100%! (In fact, at most schools it's far lower than what you might think.)

These are some questions that parents and students can be asking right from the get-go – so you can level-set expectations.

Elton Lin: I want to make sure that we have enough time for questions, so why don't you finish us off: where do families go from here? You presented a lot of information with regards to how the mechanics may work, but where should families and students start from here as they're preparing to think about the total cost? Where should they begin?

Jack Wang: They should always begin by running what's called an “EFC calculator.” (This is not the “net price calculator” on college websites; that's very different!) You want to know how colleges view your finances. However it is, that's always the best start.

How families pay for college

Jack Wang: For your question (how to begin): it should balance a number of things. It should balance, for example, what the impact is on the financial aid formula with other financial goals you might have. (You might want to retire one day. You might want to go buy a vacation home one day. Whatever.)

All these things have to work together, like income taxes. One of the things that's often overlooked is that the cost of college is an after-tax cost; you earn your money at your job, then you pay income taxes, and then what's left over can pay for college and other bills. So income tax is a huge what we call “tax drag.” There are a lot of strategies on how to lower income taxes – and then use the savings to help pay for college.

Of course, all that has to get balanced with family needs. I've worked with a lot of families who have multiple kids – so you can't blow all your savings on the oldest kid, and leave the other two to nothing! (I mean, I suppose you could… but most parents don't do that!) So you’ve got to balance all this out.

Developing strategies to pay

Jack Wang: To that end, parents often ask, “How should you pay? What should I save?” (And whatever.) I'm not going to advocate for one type of accounting or over another – but, depending on your situation, you have to think about financial aid treatment.

If you're not in line to get financial aid because your income's too high, then you don't really care whether it's counted for financial aid or not! You might not care who “owns” [the money used to pay for college]. One of the things that's out there on the internet all the time is, “Don't save in your kid's name! Don't save in your kid's name!” But sometimes it's okay – because guess what? Your son or daughter is at a lower tax rate than you are! (Which is the “tax treatment” – which is the next point.)

Or usage restrictions. Do you want to be able to use this money for other things (other than college) if they get a full ride somewhere, or if they decide not to go to college (or whatever the case may be)

And obviously you have to balance risk/reward (potential growth and risk potential).

There's no one right answer for everybody; every family is different. But I encourage you to think about all these things when families think about how to pay – because the answer isn't always, “Just stick money in a 529!” (I think that's what a lot of families default to, but it can be very different – in how you can maximize a lot of these provisions.)

Questions?

Elton Lin: I'll invite Anna to come back on – and let's tackle some questions… but I think the biggest thing here is that (with regards to planning how to pay for college) the most money is going to come directly from school. So applying to schools where you may get more merit aid is really important (and not trying to rely on outside scholarships).

The other thing is that – based on how the FAFSA is being reorganized, and how the CSS is also structured – every family is going to have their own individual strategies on how to prepare their finances in such a way to really leverage that. (I'd love for you to give some examples!)

But why don't we go to questions first – and then, if we have some time, we can talk more about some specific strategies. Anna, why don't you come in and queue us up on some questions?

Anna Lu: Sure.

One question we had kind of generally: can you elaborate a little bit more on the financial aid differences between public and private schools? For example, are private schools more likely to give grants to students, or is there not really a difference?

Jack Wang: I'll put it this way: private schools have far more leeway in whom they award money to – because it's their money, right? (I often say, “Their money, their rules.”) So there’s far more leeway in terms of whom they can give money to, and why.

Public schools have less leeway. That doesn't mean they don't have any… but they have less.

Public schools can be a great option. Some of the things I talked about still apply to public schools. It's just that the rules around the giving of grants and scholarships are a little bit more black and white. (So it's a little bit easier to figure out, on the public school side: are you going to get a scholarship or not? Because there's much less leeway.)

On the private school side is really where the difficulty is. If you go to a school like USC or Santa Clara (or something like that), they can change the rules at any time – and they fit the rules to whatever their institutional priorities are for that given year. So it's much harder to figure out. (That's when you have to end up doing a little bit more investigating on what those institutional priorities are.)

Anna Lu: And then just launching off of that (that's a perfect segue!) are these “institutional priorities”: how do you go about figuring this out? Is there a reliable way to do this?

Jack Wang: It's a lot of detective work.

I talked about some of the questions that families can ask – even in the information sessions. There are some indicators: like colleges building a brand new building. That's a pretty good indicator! Colleges do announce these at various times.

The way not to start when you're putting together a college list is to Google, “top schools for this,” or U.S. News & World Report – because those are the schools that have plenty of students for whatever major. They're not necessarily expanding. So they have less incentive to give merit aid to students going into those majors.

Elton Lin: This is also why we advocate – especially if getting some kind of merit package is important (and it probably should be important for many families) – to actually apply to more “safety” schools – where your student is in the top third of the academic profile of that school: looking at more of those schools. And then getting more of those schools to provide a merit aid package – and then having some price comparison between what school offers what.

I have this example: I had a student this year who was getting $8,000 a year to go to Purdue, and getting $0 to go to UC Santa Cruz. Would you consider going to Purdue (or going to any other university that would be offering you between $15,000 or $20,000 a year to go) over and above staying in-state?

Applying to more “safety” schools (and using that as an opportunity to compare pricing) is helpful for families.

With regards to the institutional objectives, it's really difficult… but we do have a student who was interested in majoring in business, and Rice did start a new business program about three years ago. Rice (in this example) didn't provide any aid to our student… but it did seem a hair less competitive to get into the program (than it may be for this coming year).

Understand what your goals are. I always feel like students and families should set their goals first. If a student wants to major in computer science, they shouldn't be majoring in fashion just to get a merit aid scholarship! I think you would probably agree with that, Jack.

Jack Wang: Right.

Elton Lin: You should establish your goals: try to figure out what it is that you're looking for in a school. Then, in the range of the type of schools that you apply to (that do help you still meet your academic and professional goals) open up to potentially more “safety” schools that may provide more merit aid to try to attract you to come.

Anna Lu: All right, we also have a question about 529 plans: “Is a well-funded 529 plan also counted as “income” that may be seen as not a need for aid?”

Jack Wang: 529 plans are counted as an “asset” – and so the impact on financial aid is a lot less than income. Under FAFSA rules (or FM schools) 529s (whether owned by the parent, or owned by the student; yes, students can own their own 529 plan – that is allowed) are always treated as a parental asset. So the impact's a little bit less.

However, on the private school side (especially those schools that use the CSS Profile/IM formula) there is anecdotal evidence – and what I'm about to tell you no one will ever admit to – but some schools require extra disclosure about 529s, and they do treat student-owned 529s as student-owned. So it weighs a little more heavily. Other schools will look at 529s and it will actually impact the overall aid package – because, for example, if you have $100,000 in a 529, some schools will say, “Well, 529s are meant to be spent; $100,000 divided by four is $25,000… so you need $25,000 less in aid per year!”

I've done this enough to where I've seen (anecdotally) evidence of that – but, again, no college would ever admit to that. You have better odds of getting the secret formula to Coca-Cola before a college would ever admit that!

But that doesn't make 529's bad! It's just something that could happen. For the vast majority of schools, 529s are just an asset.

Anna Lu: We also have a question about EFC calculators and net price: basically, how accurate are those? And if they aren't (or even if they are) what's another way you can gauge the college's net price?

Jack Wang: By law, every college has to have an EFC calculator on their website. Some put it front and center, others bury it deep.

I am not a fan of net price calculators for a couple of reasons. Number one: like any calculator, garbage in, garbage out, right? Some of these net price calculators can be very confusing to use. Also, several years ago, U.S. News & World Report did an article where they tested a number of net price calculators – and they found them to be very inaccurate! I actually worked with a family this year where that was the case (for a top-tier private school here in Massachusetts): the family saw one number, and the number came in totally different. So I'm not a personal fan of net price calculators. (And the quality can really vary.)

EFC calculators you can Google: there are a number of websites. The College Board itself, on their website, has a pretty nice one. But you have to know what they're asking for to put it in.

Another way to gauge the price is, on a lot of online sources (the College Board, or other websites where you get college data) they publish average net price – which is the average net price of all the families who get aid. But if you go to websites like College Scorecard or Niche they break that out – and it's actually average net price by income range. So if your income's (let's say) below $30,000 a year, this is how much you pay. If it's below $50,000 a year, it's how much you pay. All the way up: and so if your income is above $100,000 a year, this is the average of what people pay.

Depending on how far above you are (let's say the $100,000 number) obviously that's going to change your average price. But it gives (in my opinion) a much better view of what families really pay – because it differentiates by income range, which is a big driver of the aid formulas.

Elton Lin: Let me follow up with a question. This was a question posted on chat (which I think I mentioned earlier in our conversation): “Is there a public place where we can understand which colleges are giving out more merit aid (irrespective of financial need)?”

Jack Wang: There are a couple places.

The best place to get information about merit aid oftentimes is the college website itself. You typically go under “Admissions,” and somewhere under “Admissions” there's “Financial aid” and the types of aid – and “Merit scholarships” (or something along those lines). Some schools will tell you to qualify for this scholarship you need a GPA of this, and SAT or ACT of that – they're very black and white. (But of course that's not always the case.)

There is a website that's called collegedata.com – and that website has what's called the “common data set” data. I'm a little hesitant to tell people to go there, because it can be very confusing (in terms of interpretation)… but when you look up a college, there'll be a series of tabs (“Overview,” “Admissions,” “Financial,” “Student Life,” etc., etc.) If you go on the “Financial” tab, and go to the profile of the most recent class, down below there's a section on merit aid – and there'll be a number that says, “this many students got merit aid that had no financial need.” (They'll also tell you what percentage that is.) That is a place where you can see how many students actually got a merit scholarship.

This goes back to what I said earlier: a lot of parents think, “If my kid gets in, they get a merit scholarship!” Well, when you look at that statistic (off that website)… that blows up that misconception pretty quickly! You can see just how tough it is sometimes.

Elton Lin: Let's triangulate that a little bit. (And just so everybody knows, collegedata.com pools from a Peterson's data set – and Peterson's is the company that puts out the common data set that colleges pour data into.) You're saying go onto collegedata.com: under the “Financial” tab there is a percentage of students who get merit aid (who don't have any financial need, obviously). If it's a higher percentage, then the school is more apt to giving out merit aid to students who may not have direct financial need. So pay more attention to those schools that have a higher percentage of merit aid being given out.

And then, also, if you can triangulate: if you're at an academic profile where you're in the top third of the applicant pool and you're applying to a school which has a higher percentage of merit aid going to students who don't have financial need – that's probably the cross-section of schools that you may want to consider applying more to in order to get more merit aid.

Would that be a fair summary?

Jack Wang: Absolutely.

I'll give you a perfect example of that: Boston University. (I use these guys as an example often.) If you look on the financial tab, they give out merit aid; every year it varies a little bit, but it's somewhere between 10%-15% of all undergraduate students.

But then if you go on the admissions tab, they have a profile of the students whom they admitted last year: the average GPA, the average SAT… In the case of Boston University, to be in the top 25% of all SAT scores you had to have a 1520 (I think that's the number). So that's the top 25%.

But then, when you look at the financial tab, it says only about 10% of students got merit aid [for 2021-22, 21% of aid recipients received merit aid, and 5% of freshmen overall had no financial need and received merit aid]. So 1520 really doesn't cut it! The math works out to be you actually need about a 1570 to be in the top 10% (to qualify for a merit aid at Boston University)!

So this is what you're talking about: you can “triangulate”; you can figure out these conclusions: like, “The top 25% is here… but only the top 5%, 10% (or whatever percent) gets merit aid.”

The flip side is also true: there are some schools that give merit aid to (let's say) 40% of students! Well, to be in the top 25% you might need a 1400… but since they give merit aid to 40% of students, you don't really need a 1400 to be in that range. You can have a little bit lower score and still get merit aid.

This is where a family can really start to gauge their probability of getting merit aid at a particular school.

Elton Lin: I want to be mindful of time, and I'll have Anna come in with the last question… but there's a friend of mine and Jacks who's running a site called TuitionFit – where you can actually compare merit aid offers that students are getting from different universities! Maybe a little bit late for this coming application cycle, but if you're a rising [college freshman] now, and your son or daughter is going to be getting a merit aid offer, you can go on to tuitionfit.org and compare that offer with what other students are getting across the United States. (That may help you leverage an opportunity to even negotiate or bargain for a better merit aid package!)

Tuitionfit.org could be a resource. Collegedata.com is a good wealth of information. And then I'll throw it back to Anna to ask us the last question.

Anna Lu: Thanks, Elton.

This last question is about student loans. The question is: “Even if the parents can fund college for their child, should the child get a student loan?”

Jack Wang: That's a great question – and this really gets into the strategy in how families pay.

Most families think, “If I have the money saved – whether in cash or a 529 or anything else – I'll just pay it, and I won't need to borrow.” And there's nothing wrong with that. But there can be a lot of strategies to balance out some of those factors I've briefly talked about before. There are times where it actually makes sense to intentionally borrow. That doesn't mean I want to put people in debt… but (for tax strategy reasons, or what have you) there can be times where it makes sense to borrow. Every situation is a little bit different

I think, unfortunately, debt (especially student debt) has this really negative connotation – because we see the headlines: “My kids graduated with all this debt; now they can't afford to do this, that, and the other!” But debt is just another tool – and it's neither good nor bad.

If you have to borrow because you don't have enough money; you're going to a really expensive school… then, yeah, that is kind of bad. But if you actually have an integrated plan – and you're using debt strategically, so that you can accomplish another objective – then debt can be a very useful tool. I do this a lot… and in combination with tax strategy and stuff, debt can help you make money out of this whole thing – versus just be a burden! But every family is different.

Elton Lin: Yeah, and you're also alluding to the fact that if the cash that you have on hand is able to earn a higher percentage than what the interest rate might be on that loan, then that probably is where the differentiating factor will be.

Okay, I want to be mindful of our time; we're 10 minutes over.

Thank you so much, Jack – I really appreciate your time tonight. And thank you also to Anna for helping us host tonight. I appreciate everybody for joining in, and look forward to having you on our next show: we will be having other admissions-related webinar episodes coming up in the near future.

So we're excited to have you all on, and I appreciate all of you joining. All right, take care, everybody.

Jack Wang: Thank you everyone.

Anna Lu: Thank you, thank you.