Should UC Berkeley Have a Max Enrollment?

Elton Lin

Note: this is a developing story, and things may still change!

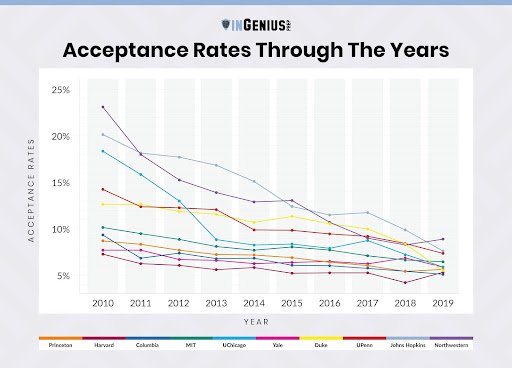

Colleges across the board are getting more and more competitive – especially among the big names. This graph shows just the past ten years:

In 2010, about 1 in 4 applicants were being admitted into Northwestern. By 2019, it was down to about one in ten (10%). And this trend of lowered admit rates is the same in every school surveyed.

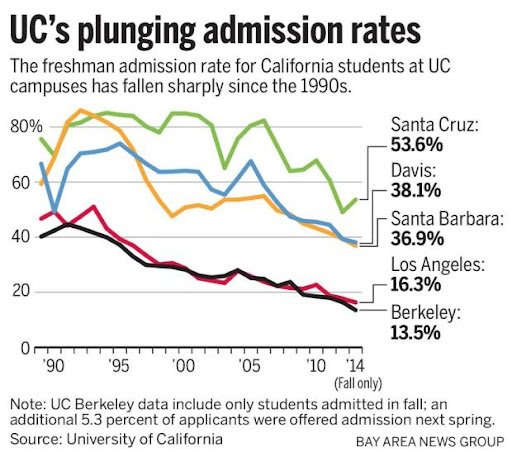

Now, UC Berkeley wasn’t displayed in the graph above, but looking at the UCs in general…

Clearly, admit rates for the UCs have also been plummeting over the years. By 2014, Cal’s acceptance rate had already fallen from 40% to 13.5% – meaning they were accepting fewer than half the percentage of students they’d accepted twenty-five years prior.

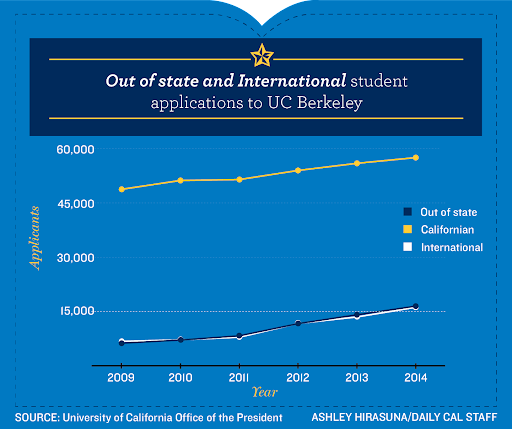

Why is it happening? Let’s take a look at a graph from the Daily Cal:

As you can see, the number of applicants is rapidly increasing. This is even more pronounced among international and out-of-state students than it is among Californians.

What are colleges going to do about this? And does it mean that the less academically successful chunk of the population just won’t get to go to college? Does it mean that the average student will be confined to community colleges, with only the crème de la crème getting onto the four-year track?

Or can the colleges just start admitting more students?

What happened at Cal?

If you’ve been keeping up with the college news at all, you’ve doubtlessly seen headlines about the California supreme court’s decision – not to overturn a previous ruling, which would cap UC Berkeley’s enrollment to fewer students that they actually admitted. This seems to imply the unthinkable: that some students who were admitted to Cal are actually going to have their offers of admission revoked and will not be allowed to attend.

It reads like every high-school senior’s worst nightmare. First a student gets admitted, and to UC Berkeley, no less, with the big, thick envelope in the mail – only for them to be told, “sorry, no can do.” And this is possibly after the student has already turned down offers from other top schools that accepted them, which have since filled their spot with another student.

While UC officials are doing their best to make sure the court’s decision doesn’t actually impact already-admitted students, the endangerment still feels present for many college-hopefuls, and enrollment for future years is also not looking too bright – a nightmare scenario. How did this happen?

The California Environmental Quality Act

It started with the best of intentions.

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) is a piece of legislation designed, as the name implies, to protect the environment. It requires that anyone undertaking a “project” in development first survey the environmental damage that this development will cause, and mitigate it.

However, one article lambasts it as being “weaponized in recent years throughout California to slow or stop development projects, including new housing and transportation.” The article goes on to explain that “California communities are rife with people who say there needs to be more housing for low-wage earners, college students and the homeless, but they want those homes built elsewhere.”

Looking at some other sources, it’s clear that this thing is being misused. Everyone knows that the best-laid schemes of mice and men often go awry… and that’s exactly what happened here.

So, what happened with the CEQA? It started in the ‘70s as a way to mitigate the harm that development might do to the environment. But mix in California’s litigious nature, and the ease of challenging any new development, and it effectively means that residents of any city in California (such as Berkeley) can oppose any new development that might jeopardize their upper-class lifestyle.

From development projects to an enrollment cap

So how does this factor into an enrollment cap?

It comes down to the perceived environmental impact of college students on nearby neighborhoods. This article explains how the CEQA led to an enrollment cap: effectively, “rising enrollment [at Cal] has affected neighboring housing, causing displacement, and creating unacceptable noise,” backing a claim made by a”neighborhood protection” group, Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods.

This was made law in 2020, when judges determined that campus expansion constituted a “project” that was subject to the same environmental regulations as a building development. This cleared the way for Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods to launch a lawsuit against the campus’s planned expansion.

So what is Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods? It’s a group of Berkeley residents who are trying to “make UC Berkeley a good neighbor.” With this as their motivation, the group made an offer to settle their lawsuit by allowing the university to admit 1000 of the 2500+ students, as long as they are “90% California residents.” This means keeping enrollment at the university to mostly Californians.

Is anyone actually being turned away?

So… the big question: is anyone who got the “thick letter” from Cal, and admission to one of the nation’s top schools actually now being told, “April Fool’s!”

As horrendous as that would be, and as worried as many high-school seniors understandably became this past week when this enrollment freeze hit the news (had their chances for getting into Cal, if they hadn’t already heard back, just dropped to near zero?): the simple answer is no. Again, UC officials are trying their darndest to make sure that this doesn’t happen. They’ve announced that every incoming freshman who they’ve wanted to take will be offered a spot.

To make this work despite the court ruling, UC plans include such things as a hybrid model that will allow some students to attend online in the fall, and then come in the spring onto campus – when some people graduate early, and others go overseas.

The workaround will allow all admitted students to either start online or defer to the sprong.

The other side

But, before we go, let’s take a look at the other side. Some of the key points made by Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods are as follows:

Berkeley’s growing enrollment is harming the city and the environment.

UC Berkeley was not designated as a “growth campus” – meaning that enrollment growth each year should not exceed 1%. However, from 2010 to 2020, enrollment increased 18%. (With a growth rate of 1% per year it should have only increased 10.46%.)

Perhaps they have some points, but it’s difficult to find much else to back Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods as an organization. They’re a small group of disgruntled people who are resistant to the rapidly expanding Berkeley campus, and to drastic change to their community and environment. But maybe we should ask some glaring questions, in light of all this, that no one is asking.

The ruling says that college undergrads have become an environmental menace. Is this possibly true? Or should we exempt public universities’ projects from needing to be subject to the CEQA? It’s an interesting conundrum, and one that will have a lot of people in higher ed scratching their heads for a while. But sometimes all it takes is a small group to raise the questions that no one is asking. And this is what Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods has done.

Online schooling has a minimal environmental impact

UC Berkeley’s workaround was to require a chunk of students to start online. Now that we have Zoom, is it really necessary to relocate students hundreds (or thousands) of miles to go to college? Or is the social aspect of college life (and the students learning to live on their own) important enough to mitigate any real environmental impacts? That’s a question that really needs to be asked of colleges going forward, post-pandemic.

Should there be caps, not on the number of students being educated, but on in-person attendance? Should schools at the university level even still teach in-person at all anymore?

There’s a lot of talk about that right now.